- Home

- Maureen Orth

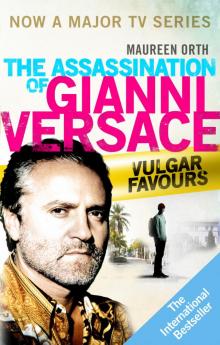

Vulgar Favours Page 17

Vulgar Favours Read online

Page 17

It wasn’t until April 1996 that Andrew visited David in Minneapolis. He lied to Norman that his sister was an anesthesiologist working there. That weekend Andrew ran into Stan Hatley at the Saloon with David, but pretended he was just in town looking around. David took him to dinner at Manny’s, the expensive steakhouse where he had once been the maître d’. Rich Bonnin was impressed by Andrew’s immaculate appearance and by how articulate he was, but David’s suspicions were growing.

Yet Andrew knew how to counter David’s doubts even before they could come to the fore. At the table with Rich Bonnin, he played the poor-little-rich-boy victim, saying what a hard cross it was to bear, being from such a wealthy family: “People are jealous, and they make up stories about you,” Andrew whined. “It was his way of trying to address suspicions about any information getting back,” Bonnin says.

In May, Andrew and David met again in San Francisco, and David got an explicit warning. Karen Lapinski, Evan Wallit, David, and Andrew took an old crush of Andrew’s from Berkeley to lunch to celebrate his getting his Ph.D. and becoming a professor. The professor says that Andrew’s dodginess had always bothered him, but like so many others, he had let it go. He was aware that Andrew “hoped nobody referenced all the ways he was cut and pasted together. I read him like a very entertaining book.”

The professor knew it had been rocky between Andrew and David. “David was just a person who demanded a lot of honesty. He wanted someone to be real with him, and that was not in the cards with Andrew.” It was a beautiful spring afternoon, so the young professor took a walk around the block with David. “Andrew is a pathological liar,” he warned him. “It’s crazy. You don’t know who he is. Don’t put anything you’re not prepared to lose in that basket.” David listened, but the professor realized he wasn’t willing to let Andrew go. “I think he wanted to make it work. He was a commitment-oriented person—very Minnesota, very trustworthy and reliable.”

Then it was Andrew’s turn to go around the block with his old friend. “I know you as well as anybody, and I don’t know if that’s saying much—you don’t tell me a lot of who you are or what your life is like in San Diego. I think I have a pretty good idea.” He looked at Andrew and said with heavy irony, “Your family’s Filipino millionaires, right?” Andrew did not rise to the challenge. His only response was, “I’m not sure I’m in love with him.” The professor considered that he had delivered two messages, but that Andrew, especially, was not going to be receptive.

“He didn’t have anywhere to fit love in, no foundation to grow, because his whole life was a lie. In order to have David, he’d have to straighten it out.” His friend wondered, “Would Andrew ever come to terms with the fact that he wasn’t all these fantasy people he had become?”

12

Breakup

IN JUNE, ANDREW hit the high-water mark of his life as a swell, sharing a house in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat with Norman and Larry Chrysler, a Gamma Mu member from Los Angeles. Andrew told David that he was joining his family at “my summer home” in France and would not be reachable for the month. Before he left he mailed David a postcard from the Helmsley Park Lane Hotel in New York: “Have the best summer and someone very far away will be thinking of you.” Once in France, Andrew continued to send David a steady stream of postcards with messages such as “France is very architectural and they have art there,” or “Avignon is still full of scamps and vamps. C’est moi, ne pas? [sic]” In another card he told David, “You’re much cuter than these hairy, dark-haired Frenchy boys … and I miss you and your jockeys more than anything.” In his postcards Andrew often made oblique references to Norman, writing “food wonderful, company less so,” and referring to a trip to Paris with his “business partner (the world’s most romantic city with the world’s least romantic guy).”

Andrew spent his days lying by the pool underlining passages in books, dining at the finest restaurants, and soaking up information “like a sponge,” Chrysler reports. He acted as the tour guide and organized all the sightseeing. He told Chrysler he was descended from Sephardic Jews. Norman listened quietly as Andrew spun his tales and gave his opinions about everything. One night they were discussing the Mamounia, the old landmark hotel in Marrakech. Chrysler recalls, “Andrew said, ‘Oh, nobody stays at the Mamounia anymore. It’s been redone.’ Two weeks later I pick up a magazine in the house and in there was the same direct quote about the Mamounia from [Yves St. Laurent’s business partner] Pierre Bergé. Word for word. He was reading tomorrow’s conversation.”

Chrysler found Andrew “fascinating” if full of “b.s.”; he knew so little French that he had to have menus translated. And he didn’t always mind his manners. Going into one bar, he bellowed, “Here come the rich Americans!” He apparently did not know the area as he claimed to, but he would point out a distinctive house and say, according to Chrysler, “That belonged to so-and-so, and then it was sold to so-and-so.” On the subject of cars he was obsessed with Mercedes: “I always had a Mercedes.” One day he came back from the village of Beaulieu with a tiny jar of jam that had cost twenty dollars. “I never look at any price,” he said. “My family never looked at any price.”

On their way back from France, Norman and Andrew spent several days of July 1996 in East Hampton, on Long Island, as the guests of a wealthy gay couple. They attended parties and dined at the trendy restaurant Nick and Toni’s. As usual, Andrew charmed his older companions, but according to one of his hosts he said “inappropriate things about money” and told them stories that made them raise their eyebrows. He said that he had been married to a Jewish woman and that his father-in-law was the head of Israeli intelligence, the Mossad. “He was young and attractive, entertaining, good company—what’s not to like?” said the host, who also found him “sad” on two levels: “He’s got a lot going for him, I thought. He doesn’t need all this sham … He was also ultimately a young man with no career ambitions in any direction. He pretty much said he was interested in older men for their financial situations. He made no bones about that, and he would say it in front of Norman.”

Norman apparently did look at prices. While in Europe, Andrew had decided that he should have a new $125,895 Mercedes SL 600 convertible, and even confided to David about the car in a postcard. “I may finally get my Mercedes SL 600!” he enthused. “I feel I deserve it even if nobody else does.” Soon after they returned home, however, when Andrew told Norman he would leave if he did not give him the car, Norman refused. In a grand gesture, Andrew packed his bags and left a note saying, “I’ve moved on.” But he also left the voice-mail number of his cell phone and fully expected it to ring immediately. Negotiations broke down, however, and Andrew had to move into a weekly studio-apartment rental on Washington Street in Hillcrest—about as far away from 100 Coast Boulevard in La Jolla as you can get. Furthermore, Andrew had been promising David for months that they would watch the fireworks on the Fourth of July together from a sailboat in Boston Harbor. But in June he sent David a postcard from Cap-Ferrat, suggesting unnamed sinister activity might keep them apart: “The situation in Marseilles has become extremely delicate and I may not be home in July.” Later he wrote, “I may not be home July 4th.” When Andrew didn’t come through for the fourth David finally had had it. He, too, cut Andrew off.

Both blows were stunning. Andrew had demanded a new Mercedes because that was the level of living to which he was accustomed, he told friends; Norman should honor that. After all, by living with Norman, he was forfeiting his inheritance. His family was disowning him, he said, because “by caring for Norman” into his dotage, he was effectively outed. Many of his younger friends actually believed this story. “He felt he came down several steps in his relationship with Norman,” says his ex-roommate Tom Eads. “He felt he should be flying first class. He felt he was giving up a lot. He gave up his inheritance to devote himself to Norman. Andrew didn’t like the nickel-and-diming. They argued over decorating. Norman would only repaint so many square feet of the new house

in La Jolla. He wouldn’t repaint it all.”

Robbins had thought Andrew would stay in the arrangement at least three or four years—that was Andrew’s thinking when he and Norman first moved in together. But Andrew wanted control at least as much as he wanted money. It rankled him that Norman, who, he told people, was worth $110 million, wouldn’t fly first class—he wouldn’t even fly business class. Flying coach was a low blow to a narcissist like Andrew, even if he and Norman stayed at five-star hotels and ate in three-star restaurants. In a fit of pique, Andrew listed his demands: a Mercedes, first-class air travel, an increased allowance, a place in Norman’s will. Norman was willing only to increase his allowance. “Andrew really thought Norman would collapse without him and beg him to come back,” says Tom Eads, who termed the ending, “a deal not continued.”

Andrew next wrote Norman a letter stating that he would leave it up to him to decide the amount of palimony he should receive to compensate for his year of service. Norman gave him $15,000 and took off for Europe on a previously planned vacation with friends Andrew had introduced him to. Andrew apparently tried to deposit the money without having the bank give the standard notification to the IRS—any check in excess of $10,000 must be reported by law—but the bank teller he knew refused his request.

Now that he was cut off from Norman, there was no way Andrew was going to let David go. But David had long suspected that Andrew was mixed up in something shady. Playing the big shot, Andrew had once told David, “There’s someone in prison right now who got my friends in trouble, and I’ve arranged to have him killed.” David had no idea what to think, but such remarks bothered him.

On several occasions, David had brought up the possibility of ending their relationship. “You know, if you don’t want to see me anymore, we don’t have to keep doing this.” But Andrew would send him a dozen roses at work to placate him, while refusing even to consider that their relationship was over. “No, no, no. Our relationship is too special to me.”

Now Andrew begged David to visit San Diego, but David refused. It was beginning to sink in—Andrew had lost both Norman and David. Moping and aimless, Andrew next turned to Jeff, the second most important person in his life. He showed up in San Francisco just as Jeff was quitting the California Highway Patrol—it just wasn’t what he’d expected.

Andrew said he was planning to stay just a few days, but his visit stretched into two weeks. Jeff lived on and off with his eldest sister, Sally Davis, in nearby Concord, California. Mostly, however, he was apartment-sitting with his latest catch: Daniel O’Toole, a twenty-one-year-old, blue-eyed blond. Jeff had told Daniel he was in love with him a couple of days after they met. Daniel fell head over heels for Jeff, too, but he worried that Jeff seemed to want to control him.

Daniel had his first prolonged exposure to Andrew when they bumped into one another one afternoon in the Castro. Andrew, who was wandering around the neighborhood, invited Daniel to lunch, flashed a lot of money, and suggested that they both get haircuts. Andrew had his hair closely cropped—“just like Jeff’s,” Daniel said. “It seemed to me that he was copying a lot of Jeff’s looks.”

Andrew then managed to get Daniel drunk and took him into a video store, where he pawed through “stuff that looked like underage exploitation.” Andrew picked out some raunchy bondage porn that was kept in boxes in the back, deemed too raw for the shelves. After another drink, Andrew took Daniel to his Infiniti parked nearby to show him a picture of David and listen to music as Andrew rhapsodized to Daniel about David—“the love of my life, the man I want to marry.” He also told him the story of having a daughter in San Francisco. “It seemed to me that David knew Andrew so well. Andrew implied that he had an extensive relationship with this person.”

When Andrew dropped Daniel off at 11 P.M., Jeff was waiting. He was livid at Andrew for getting Daniel drunk. In fact, Jeff was rapidly getting fed up with Andrew altogether. He called Daniel’s mother to apologize, telling her in no uncertain terms “to do anything you can to keep Daniel from getting mixed up with Andrew.” She asked when Andrew would be leaving. “Hopefully soon,” Jeff answered. Daniel recalled for Jeff some of the things Andrew had told him about his daughter. “Oh, Daniel, don’t listen to all those things. He tells a lot of things that aren’t true.” Daniel says, “Jeff didn’t figure there was any mystery to Andrew anymore. His ideal situation was to rent a movie, go pick someone up in a bar, and bring them back to his hotel room.”

Jeff told Daniel that Andrew embarrassed him in public. Andrew would start telling one of his exaggerated stories, and all of a sudden he’d put Jeff into it, expecting Jeff to back him up. But Jeff did not want to listen to lies, and certainly did not “want someone else to determine what aspects of his personal life to be revealed.” But then why did Jeff take so much from Andrew? Daniel wanted to know. Jeff’s excuse was that “he felt sorry for Andrew because Andrew considered Jeff to be his best friend. But Jeff didn’t consider Andrew to be his best friend.”

Nevertheless, Jeff was loyal. He also admired Andrew’s generosity, whether or not it created a sense of obligation. He counseled Daniel that it was best just to let Andrew pay for everything. Otherwise he’d make a scene, and that was just too exhausting. But by then “Jeff was definitely tired of the act,” Daniel says. “I don’t recall a time I knew Jeff when he was comfortable with Andrew, when Jeff and Andrew were really close.”

Late that spring, Andrew, David, Jeff, and a date of Jeff’s had dinner with Doug Stubblefield and his friend Glen Setty at a sushi restaurant. Andrew was especially loud that night. He said how Jeff was his oldest friend, and they had known each other since kindergarten or first grade, so if anyone had any doubts about what Andrew said, they could ask Jeff. Jeff politely went along. He said, “I grew up on the other side of the tracks, but I know everything about him.” Andrew said, “If you want to get the real scoop, go to Jeff—he has the dirt.” Stubblefield says he felt a real sense of camaraderie between the two that night, but in fact, Jeff would later tell others that by asking Jeff to lie for him, Andrew had in fact pushed Jeff away.

Jeff went down to San Diego for Gay Pride Weekend in July, and he and Andrew bumped into a naval officer who had known them both for a long time. They had dinner, and for the first time the officer noticed that Jeff’s comments to Andrew were edgy. He guessed that maybe they were fighting over a boy, but that wasn’t the case.

Andrew made one last stab at trying to woo David, in San Francisco around Labor Day, but he failed. David demanded honesty, and Andrew couldn’t unmask himself. He had created this phony persona that destroyed his ability to have a real relationship. Without the facade, who was he? In a community where looks and cash came first, Andrew was suddenly on the losing end where both were concerned. His image, so carefully and pathologically created, was crumbling, and his sugar daddy was gone. Now he had to face the fact that David was gone too.

Defeated, Andrew flew south for the holiday weekend. When Michael Moore picked Andrew up at the San Diego airport, he recalls, “he didn’t say anything for a long time.” An old Bishop’s School buddy, Stacy Lopez, heard more. When she ran into Andrew at a Labor Day party, the first time they had seen each other in several years, she ran over to hug him. At first he hesitated answering her questions about what he was doing, but she pressed on. “Do you work?” she asked.

“No,” he answered. “I’ve got money.”

“Oh, you’ve got yourself a sugar daddy, huh?”

“I’ve got my ways.”

“Have you been dating?”

Andrew didn’t lie this time. He told his old friend Stacy the truth. He was devastated, he said. “I was in a relationship that really hurt me.” He was embarrassed that he had put on weight and told her he felt very unattractive. “Just look at me. I’m awful. I’m horrible.”

Stacy remembers, “He was not happy with himself.”

The unraveling had begun.

13

Bad Manners

AT THE END of October, unable to find a job in San Diego, Jeff culminated a three-month search by landing a job in Minneapolis as a district manager for commercial accounts at Ferrellgas, a propane company that actively recruited ex-military people. Some of Jeff’s friends, such as Michael Williams, tried to discourage him from leaving: “Jeff quitting so fast and moving so far, I was bothered by it and trying to talk him out of it.” But Jeff was anxious to repay money he had borrowed from his parents, and promised friends he would come back in six months.

Even though Jeff had supposedly cooled toward Andrew, in September he had allowed him to fly along with him to a job interview in Houston. Jeff did not want to be alone. Now Jeff was leaving a warm and sunny place he loved to live in a far harsher climate. The news that Jeff would be in Minneapolis was all the incentive Andrew needed to mount a new campaign to reinsert himself into David’s life. He called David’s loft, and David’s sister Diane Benning answered. “Don’t even call him back,” she instructed. His sister had warned David not to have anything to do with Andrew. But Andrew persisted, with the excuse that David could help show Jeff around. The only problem was that a few weeks before Jeff got the job, David had fallen in love with someone else.

Robbie Davis was a tall, self-described “BAP”—Black American Prince—from Washington, D.C., whose family owned a thriving commercial cleaning business. Robbie was cool and street-wise, the first of several black boy-friends David would have. “They came from a different upbringing, and he found that very intriguing,” says Wendy Petersen. “He felt he had had bad relationships at the time, especially with white guys. He felt he had been stabbed in the back, stepped on, or taken advantage of.” David also sympathized “with many of the minorities’ struggles,” says Monique Salvetti. Wendy believed that having a long-distance boyfriend suited David, who could be aloof when he wanted to be. He felt that distance gave him more “control.”

Vulgar Favours

Vulgar Favours