- Home

- Maureen Orth

Vulgar Favours Page 3

Vulgar Favours Read online

Page 3

MaryAnn kept the house spotless per his orders—there were plastic runners on the carpets—and stayed home most of the time. She devoted herself to her kids, and when she was alone with them, things were often pretty happy if precarious: Too much pressure could trigger a breakdown. But the Cunanans did not socialize a lot and had little interaction with other people on the block. The neighbors considered MaryAnn nice but somewhat eccentric—with her hair pulled back in a tight bun, wearing layers of clothes even when it was hot, and apt to say the first thing that popped into her head in a childlike voice. She had trouble with her weight and would attempt various diet programs to reduce. Rarest of all in California, she did not drive the freeways but stayed on surface roads.

Most of the driving she did was to church and back. MaryAnn was a very religious Catholic who sent all of her children to Mass on Sundays as well as to catechism class. She hoped that someday Andrew would become a priest, another point of contention with his father. He did become an altar boy, and the trappings of the church, at least, seemed to exert a strong influence on him.

Given the almost perfect climate in Bonita, most kids lived outdoors year-round, riding bikes, playing kick the can, catching lizards in the nearby canyons, playing baseball. Not Andrew. He preferred to be indoors with his mother, reading the encyclopedia and watching TV. “He loved Audrey Hepburn and Katharine Hepburn,” MaryAnn says. Another favorite of his was Robin Williams’s TV sitcom Mork and Mindy. Andrew would recite Williams’s manic dialogue by heart. Andrew’s neighbor Scott Ulrich remembers once yelling for Andrew to come outside—they needed more kids for one of their games. Andrew came to the door, but his mother pulled him back. “You can’t do that,” she told him. “He was more of a loner,” says Ulrich. Charlie Thompson, another neighbor, calls Andrew “the epitome of a mama’s boy.”

Andrew’s relationship with his mother was complicated. Her personality was fragmented, and after having been used as a doormat by her husband for years, MaryAnn was both needy and smothering. She brags that when Andrew was a little boy they “were inseparable.” Since Andrew’s parents vied for his attention, MaryAnn’s closeness to Andrew infuriated Pete Cunanan. “You cannot cling like that to your son,” he says. “She suffocated him by his necktie. She clung to his belt loop. It was that kind of relationship—mothering in a different way.”

Perhaps MaryAnn thought the other neighborhood kids were too rough, but by keeping Andrew apart and to herself, to dress up and dote on, she was helping create a personality who began to see himself as superior, which his father encouraged. “The one impression I got from Andrew back then is he knew something good would happen to him. He knew he would turn out better than his peers, than everyone around him,” says Gary Bong, Andrew’s junior-high classmate. “This sense of superiority was his defining characteristic.”

Pete also lavished attention on Andrew. They had pet names for each other and baby-talked with each other even after Andrew was well into high school. Pete says they would refer to certain funny things as “coocoo or poopoo. He was more than a son to me. He was a friend. We’d kick tires together. We’d loaf around. I’d say, ‘Hey, kid, let’s go for an ice-cream ride.’ He learned very quick … Of course, the first thing I did with him is throw Amy Vanderbilt at him. I said, ‘I want you to memorize every fuckin’ period and comma in there.’ If you grow up in this society, you’ve got to give yourself a walking cane, to be a cut above the rest.”

“Of all the children Pete has, he put so much attention toward Andrew, maybe because he thought Andrew was so good-looking. It was not healthy,” says Delfin Labao. “His father spoiled Andrew, made him feel he’s got to be somebody, and maybe that rang a bell in his uncertain mind that that was what life was all about.” Pete was beginning his bumpy career as a stockbroker. After being so proud of his training by Merrill Lynch, he didn’t stay there. He left after two years to work for Prudential Bache. He lasted there only thirteen months before being “terminated for non-compliance,” meaning he was fired for breaking the rules. But no one would ever know that he was having problems from the way he treated his son.

On their ice-cream rides Pete would tutor Andrew on labels and image. “He knew I made some money. We’d stop by a store and I’d say, ‘You want those Ballys, those Johnston and Murphy shoes, a Cerutti jacket? Hey, you like the blazer?’ He’d say, ‘Gee, Dad, look at this one!’”

At an early age Andrew dressed in suits and preppy clothes, much more formally than most children his age. He liked to be noticed. “He was always a loud kid, very boisterous,” says Charlie Thompson. On the school bus, Andrew would speak in loud tones from the back so that the other kids would be forced to turn around and look at him. He was mimicking his father’s bravado, but that didn’t necessarily mean that he felt secure.

AT BONITA VISTA Junior High, which began with seventh grade and ended after ninth, Andrew became part of the MGM—mentally gifted minor—program. In order to qualify for the accelerated academic course, one’s IQ had to be at least 132. In the third grade at Sunnyside, Andrew’s IQ tested at 147.

Bonita, a sprawling hilltop structure with ten full basket-ball courts and three soccer and football fields, was socially very competitive. The elite of the school were divided into the “soshes,” or the social kids, and the “smacks,” the smart ones in the gifted program. Andrew was a smack, and a rather showy one. Pink and black were the big colors during Andrew’s years there, 1981–83, and students voted on who was best dressed. Andrew, perhaps taking his father’s and Amy Vanderbilt’s admonitions altogether too seriously, was beginning to define himself by cultivating an image of wealth and breeding. While most kids wore jeans, Andrew set himself apart by dressing in pressed khakis and Izod shirts. He wore an argyle vest and Sperry Top-Siders and put dimes in his penny loafers. His aim was to portray himself as a sophisticated, eastern, boarding-school student in an area where most kids considered Colorado “back East.”

By seventh grade Andrew had developed a line of patter and a penchant for telling stories based on what he had read, and embellished for effect. The disturbing grandiosity that would mark his personality had already begun to take hold. No one knew he was half Filipino, and he never befriended the other Filipino students. “He always wanted to be part of a richer crowd,” says classmate Gary Bong. “Andrew said he owned a lot of stock in junior high,” remembers Andreas Saucedo, now a stockbroker himself. “He said he owned Wrigley Chewing Gum and Coke. He was always saying, ‘My father did this and I’ve got stock in this.’ I thought to myself, God, I want stock!” The fact that Andrew’s parents never showed up at school and that almost no one was ever invited to his house shielded him. He would even often wait outside his house if he was being picked up. He clearly did not want his myth to be shattered.

A lot of Andrew’s classmates got a kick out of his ability to con them and to tell funny, colorful stories—he had picked up enough information from his reading to be able to make himself stand out in a crowd. Girls especially found it easy to talk to Andrew, because he was interested in celebrity and fashion. But Kristen Simer notes, “Even back then he was a pathological liar. We didn’t take him seriously.” And to some he seemed bizarre—flamboyant and stuffy at the same time. “In those days preppy meant sissy,” says Charlie Thompson. “People would whisper on the playground, ‘He’s a fag,’” says Lou “Jamie” Morris, who had known Andrew since first grade.

Andrew began to hang out with Peter Wilson, a pudgy only child who became his adoring sidekick. Together they memorized The Official Preppy Handbook, taking it more as the Bible than as satire. At Christmastime the two were driven to a local mall to shop, but they blew all their money on lunch in the Neiman Marcus shoppers’ dining room—in Andrew’s mind, the height of chic. Perhaps because MaryAnn was a good cook, Andrew, who later became a connoisseur of restaurants and a gourmet of sorts, showed an early interest in food as a manifestation of his snobbery. When Mrs. Wilson asked what she should serve for Peter’

s Halloween birthday party in the eighth grade, Andrew floored her by suggesting cracked crab. “I was thinking pizza,” she said.

It was a costume party, and Andrew came as the Prince of Wales, dressed in a blue blazer with a crest and a silk ascot. He suggested to tall, pretty, blond Jennifer January, a friend from the MGM program, that she come as Princess Diana. The fact that Jennifer looked a great deal more like Diana than Andrew looked like Charles was of no matter—in Andrew’s mind he was a prince. “He put on an air—‘I’m royal.’ And he was. He carried it off,” says January. “I think he was looking for something a little better than what he came from.”

Andrew called Jennifer’s father, a retired navy pilot, to ask if he could take his daughter out to a lobster lunch. Her father refused. Not to be deterred, Andrew invited her to have the same lunch with him at school—clam chowder and lobster with rice and drawn butter from a nearby seafood restaurant. Jennifer was mortified that he offered this expensive spread to her in front of all the other kids, who were eating out of their brown bags. Worse still, Andrew’s mother delivered the meal. When Jennifer asked Andrew how he had gotten his mother to bring such an elaborate lunch to school, he said, “I told her to buy it and that it had to be here right on time.” Today January says, “I felt she was controlled by Andrew. There was never a question he ran the show.”

Sometimes Andrew’s instructions on what it took to become a worldly sophisticate grated on people’s nerves. At Lou Morris’s twelfth birthday party, Andrew complained that there was no Perrier to drink, only tap water, and he told the Morrises that the salad should be eaten after the meal. “That’s the European way,” he said. But, unlike his classmates, Andrew never reciprocated with parties of his own, and Morris, who knew Andrew from the fourth grade on, finally got fed up. He was sick of inviting Andrew to his house and never being invited back in return. Who was Andrew to put on airs? Morris was the one with the big house who was asked to the invitation-only Junior Assembly dances—not Andrew. “I always knew the family didn’t have as much money as he let on,” Morris recalls. “He would say he spent the summers in Europe. It was all lies.”

Morris says he could see that Andrew’s values were becoming distorted. “I stopped being friends because he’d be loud and obnoxious, and he became so materialistic and preppy. He put other people down.” Lou was shocked when he and Andrew were in the school yard one day and Andrew pointed across the hillsides to the dramatic canyons overlooking the Pacific. On clear days you could see north to downtown San Diego and south to Mexico. “If someone were smart, they’d put condominiums up on all those hills,” Andrew said. “You could make a lot of money.” Lou was appalled. Those were the cherished open spaces they had grown up with, and every day developers were threatening to encroach. Why would anyone want to spoil such pristine beauty? (Since then Andrew’s vision has come true: There are identical tract houses all over those canyons.)

Because Andrew was clever and upbeat in class, most of his teachers genuinely liked him. He was always very polite to older people. As for his pretensions, parents like Mrs. Wilson thought he’d get over them. Mrs. Jerelyn Johnson, Andrew’s English teacher, viewed him as “very verbal and one of my better writers. He was very bright, among the brightest, and I get the best and the brightest.” For one class project with Mrs. Johnson, Andrew, Peter Wilson, Jennifer January, and Jennifer’s pal Kristen Simer acted out a passage from The Great Gatsby. Andrew, ironically, did not portray Jay Gatsby, the great aspirer; he played Nick Car-raway, the narrator.

Religion was becoming an increasing source of conflict for Andrew. He was growing up under the tutelage of his mother in a strict Catholic household. The Gospel was not about Cerutti blazers and Bally loafers; what was wrong and what was right were clearly defined. But Andrew was getting mixed messages. If he really was special and superior, perhaps the Commandments didn’t apply to him. On the other hand, he was beginning to feel attractions for other boys, and those feelings had to be suppressed if they were sinful.

To his family, Andrew gave no hint of any such internal struggle; in fact, he made quite a good impression on a nun from his parish, Sister Dolores, who led Andrew’s catechism class on a field trip to a Mexican orphanage just south of the border in Tecate. Unlike the rest of the kids, who were content to drink McDonald’s orangeade on the way, Andrew took his own cream soda on the drive down; “He said cream soda was posh,” Jennifer January remembers. But once there, he seemed to be deeply affected, spending a happy day with the children, giving them piggy-back rides and playing soccer. “He had an awakening experience,” Sister Dolores says. “He told his mother he had a calling from God; ‘I want to become a missionary.’ He got such a thrill helping little kids. He thanked me for letting him go. He was so grateful. His mother wanted to send him to Catholic schools—his father said no.” Sister Dolores adds, “You move hundreds through for one hour every week. He stood out.” On the other hand, she had no illusions about the Cunanan family. “Right from the beginning it was a dysfunctional family. Between the mother and the father, the kids were tossed back and forth. They didn’t have any money. MaryAnn was one hundred percent Italian, and he was Filipino. It didn’t take. Andrew picked up that to get ahead in this world you have to own things.”

WITH ANGER CONSTANTLY boiling beneath the surface, the tense situation at home was a trial for Andrew. Despite all the attention he was getting from both parents and their unspoken affirmation that he was the crown prince, he was being asked to shoulder an enormous burden; they expected him to justify their staying together, perform according to their expectations, and become either a priest or a rich socialite, though he was without the resources to do so. From early childhood on, there were several Andrews: the happy kid, the worshiped baby idol, the growing boy being drawn into an adult world that was filled with problems. What child wants to marriage-counsel a clinging mother or calm down an abusive father? On the other hand, if he had authority over his parents, it would be easy to break the rules and go beyond the established bounds.

Still, there were so many secrets he felt he had to keep. They began with the apprehension he felt coming from a racially mixed family, which in the seventies, in that community, was not as readily accepted as it is today. His mother’s embarrassing illness, his father’s explosive, unpredictable temper and brutal treatment of his mother—in one way or another, the whole family suffered from the parents’ sick dynamic. Some of the kids have had to battle eating disorders and substance-abuse problems. More than one family member had threatened suicide.

Elizabeth Oglesby, a psychologist who later lived next door to Andrew in Berkeley and befriended him, believes that Andrew was a narcissist. “Narcissists look at people as objects they can consume or use. His parents were just there to serve, adore, or cater to him.” It is not unusual, according to psychotherapists who have studied narcissism, that in unhappy families the mother may choose a son to lavish her attention on and may use him almost as an emotional stand-in for the husband who has rejected her.

The perils run deep for such children, according to Oglesby. While their loyalties are torn between their parents, they are taught that they are superior, little Prince Charmings. Yet they are not able to process such feelings of intimacy—which include elements of seduction, whether there are sexual overtones or not—so they end up pushing down their confused feelings of guilt, fear, or anger in an effort to avert them. When feelings are repeatedly suppressed they end up not counting for much. What is left in their place is a certain coldness, along with the idea that one’s image is more important than having feelings at all. The explosion comes later, when the child is unable to get his way; then the image crumbles, and all the pent-up rage erupts.

A FEW MONTHS after Andrew’s own bloody explosion, Pete Cunanan decides to return to the United States for the first time since 1988, when he “flew the coop,” leaving his family feeling stunned and abandoned and selling their house out from under them. Pete has flown in from the

Philippines to tape a Larry King interview. In emulation of King, known for wearing colorful suspenders, Pete is sporting suspenders with a Golden Gate Bridge design. His gray sport shirt with a tab collar looks expensive, and it covers the paunch that hangs over his belt. His dark eyes are alert but puffy, the latter intensified perhaps by jet lag. MaryAnn has accused him of embezzling more than $100,000 of clients’ funds and fleeing from the law; his former boss claims he filed a complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission about him. Pete maintains that he was never officially charged with anything, and that the statute of limitations has run out anyway.

Pete wants to snag a book-and-movie deal about Andrew. He has run the numbers, he says, and his movie would cost eleven and a half million dollars to make. He also has a “most optimistic” analysis of the film’s gross, “$115 mil” and a “least likely … $34 mil.” He is asking $500,000 for the rights. The title is A Name to Be Remembered By. “I will not agree to anything else. That was his dying wish.” Pete insists that he was in communication with Andrew to the end, and that the few intimations about Andrew’s story are just “a teeny whiff of what the whole pie is about. If I smell money, this is it. It’s prestige on the line. It’s power.” However, he can have no contracts within U.S. jurisdiction. “America’s laws don’t breathe without creating liabilities.”

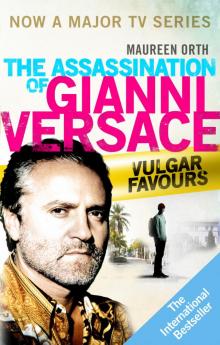

Vulgar Favours

Vulgar Favours